Introducing SERO 2.0- The Rise and Vision-Part 1

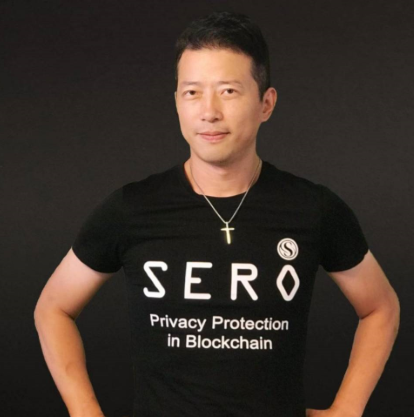

As SERO continues to grow and deliver solid privacy solutions consistently, COO of SERO Mr Jason Pope presents a sneak peek into what and how he envisions SERO and crypto currency blockchains in general and lays out how SERO 2.0 is being developed via this three part series.

Part — 1

Chun Xiao (Dawn of Spring)

Financial Leverage, Market Liquidity, and Bubbles

The main purpose of financial leverage is to lift the utilization rate of available funds, where by amplifying investment or operational gains or losses. The basic mode of financial leverage is lending and borrowing, which can often be embedded in many forms of commercial contracts and agreements, which, alone by themselves, may or may not create asset bubbles that eventually burst. But if such leveraged products are brought to open markets for free trading, then the excessive liquidity provided by these markets often induce bubbles.

For example, you want to buy a 5kg watermelon that costs 100 Yuan presently, and you are just short of the money. While the melon farmer doesn’t want to sell you the 5kg melon at hand, he does want to get cash liquidity urgently. He offers you a choice that you can pay him 90 Yuan (what’s in your wallet) now for the same 5kg melon that you can pick up one month later. This arrangement is a “cash settled forward delivery contract”, where you take advantage of a situation and are able to pay a discounted forward price for something that you have to consume later.

But from the farmer’s perspective, if he took 90 Yuan and promised to give you something in the future, he essentially borrowed 90 Yuan and was obligated to give a specified product as repayment — financial leverage thus occurred through this arrangement. If the 90 Yuan per 5kg forward delivery trade has a substantial profit for the farmer, and there is a very efficient market for such forward contracts, then all melon farmers can start growing watermelons and start looking for buyers of 90 Yuan to lock in a future profit. If the strong interest of selling “future melons” is observed by many traders who neither want melons nor grow melons, they may speculate that there aren’t enough melon consumers out there to sustain the 90 Yuan price level when all the farmers dump their melons. So these traders may decide to race ahead of the farmers to sell the “future melons” that they don’t actually grow. Now assume you, the one who originally started this product, seeing the same supply pattern,start to think that this may be just the beginning of plummeting and you might be able to buy the same melon at much lower price. So you tell the farmer to cancel his obligation of giving you the watermelon and just pay you back 89 Yuan, which he agrees with a smile because he has just borrowed 90 Yuan from you for a negative interest rate, which is the same as “covering a short position” with profit.

Meanwhile, many things can happen to all the melon farmers as a whole. Things such as weather conditions or fertilizer costs can add more complications on top of the turbulence caused by the “future melon” contract they are engaged in. But one thing is for sure, that the existence of such a leveraged product has encouraged them to grow melons, and because this product is easily accessible to anyone who is not in the melon business, it also dramatically increases the uncertainties for the farmers.

An originally very basic financial leverage transaction gives birth to a leveraged product, and then the free and open market creates massive liquidity of this product, which then in turn causes the real participants — the farmers — much undesired and unexpected consequences. If growing melon requires a tremendous of effort, then the easy access of such products eventually can cause the farmers to doubt its usefulness. The end result is that farmers will stay away from this leveraged product, leaving only the players who have nothing to do with melon business in this zero-sum bubble. The melon business won’t fail because of that, but the “future melon” product will.

The Nature of Different Tokens

Stocks are essentially issued accounting certificates of a company’s operational performance, which is equivalent to the “future melon” product of melon farmers. But unlike the dubious future melon product, there are strictly maintained regulatory systems overseeing stock markets, and there are well established rules on data and information disclosure regarding the listed companies, including trading data in the exchange markets. Therefore, the deviation between the stock prices and the future earnings value of the companies’ is relatively limited, or better understood. However, since the crypto currency market is still in a period of hyper and crude growth, coupled with the lack of standard trading framework, it is common to have dramatic deviation between a token’s price and its long-term value, if it exists at all.

In order to establish a rational framework for analyzing crypto tokens we would categorize them into Security Tokens, Utility Tokens and Equity Tokens. Many investors often do not understand what kind of tokens they are dealing with when investing in crypto currencies.

Security tokens can be understood as the representation of ownership of other assets such as traditional securities, real estates, precious metals, or other tokens, etc. Their intrinsic return can exceed that of the underlying assets, through mapped ownership within the tokens, say, the rights to lease income from a building. It is critical to establish that the rep mechanism is legally sound, i.e. that the tokens you own indeed represent the rights to the underlying assets, strictly accepted by law. Theoretically speaking, changes of these token’s values should reflect what they represent.

Utility tokens can be fully understood as commodities, namely that they are practically useful in some way, and the investment logic thereof is basically governed by the supply & demand relationship of such utility over a period of time.

Equity tokens can either be thought of value storages by themselves (or Asset Tokens), or represent something equivalent to equity stocks of companies, often start-up ones. As such, most of the ICOs are basically schemes of equity financing through selling tokens in exchange market under the banner. It turns out that the values of such tokens are often the most unreliable due to the serious lacking of regulations, as there is simply not enough necessary data for investors to judge the value of these companies or projects. Particularly in China, where investor education has yet a long way to go, many token schemes exploiting human nature have been tried and tested repeatedly, and the immaturity of this emerging sector is likely to cause serious damage to the healthy development of the overall market place, as each bubble is often accompanied by deep-cut injuries beyond flesh wounds.

The Tokens of Public Blockchain

A public blockchain requires the participation of the underlying consensus maintenance to operate properly, but where does the value of the tokens, used as the incentives for consensus participation, come from?

We think Bitcoin is essentially an Asset Token by itself. There are three characteristics that can support this view. First, very much like the few commodities in physical world, Bitcoin has nothing to do with its practical usage value; secondly, it has a fixed amount of total supply; and finally, the price of Bitcoin is entirely determined by the accumulative recognition achieved during its continuous circulation.

As to ETH, the first launched public blockchain supporting smart contracts and programmability, it is very far-fetched to define it as an Asset Token, or it is very contradictory to its original positioning. ETH is mainly designed to address the cost (the gas) of data transmission on the public network. Since it has been defined with a clear practical usage, its value should be determined by the demand of such usage in the market (unfortunately, though, the current pricing of ETH can hardly be said so).

Yet in fact, almost all the token production patterns on public blockchains are pre-set in advance to the very beginning, which begs the question: can we know the process of ecological development from the beginning? The answer should be obvious that it is unrealistic to accurately predict the market size and structure in such an emerging technology sector. Therefore, very often the price fluctuation in token markets is determined by the capital flows in and out of the tokens themselves.

But should capital flows be the main driver of token pricing (here let’s recall the “future melon” example)? To a large extent, the market price of tokens must be interfered by the rapid profit-seeking capital flows, because we must acknowledge that they are making block chain technology a great focal point. Meanwhile, it is precisely the influence of such capital flows that obscure much of the essence or nature behind many tokens’ valuation. In a market where the early regulatory system is not yet available, it is difficult to find a way to evaluate whether token price is reasonable. But we still hope to find a public chain consensus mechanism that at least attempts to quantify the structure of various ecological demands for the tokens within the network, and properly link the mining output to such quantified structure along the way of the ecosystem’s development.

Tokens and Metals

So far, the best analogy we’ve come up with to describe crypto currencies is metals. If you think of Bitcoin as gold, which nearly has no practical value, while other crypto currencies compete for the positions of other metals, you realize that there are few precious metals such as gold whose practical value can be completely unequal to the market price. The financial statues of most other metals are almost certainly linked to their industrial usages and productions. Even silver, a precious metal that has long been considered and expected as a pure financial asset along with gold, has seen such statue in decline, and slowly its price has been more determined by the performance of its industrial value.

Just as with most metals, from an investment point of view, we should pay closer attention to the performance of utility token’s practical usage, and regard it as a foundation to predict its future supply & demand in the market. Here it must be mentioned that we are not suggesting predicting a physical commodity’s utility value is easy. The prices of metals have fluctuated sharply throughout the entire financial history. Take copper for example, it is actually very difficult to predict the copper price movement in short term, because the change in demand of copper and the corresponding supply side response have too many intertwined and often conflicting factors to be analyzed accurately. Therefore, valuations of copper, even though as a utility metal, can be in the hands of speculative capital flows, sometimes even for prolonged periods. But whatever short term influence of capital might be, we also know for long term that copper holds base values that cannot be questioned.

Fortunately, the analysis of market supply & demand of a crypto currency of non-asset type is simpler, because in this very particular emerging industry, if a crypto token is viewed as having commodity attributes, then presently or in the foreseeable cycles, the applications using such commodity are relatively uniformed, while its output, circulation, distribution, and the associated costs are relatively transparent. Setting aside the speculative factors of capital flows, long term investment analysis can focus on how to grasp its utility value in the foreseeable future. In contrast, analysis for long-term investment of tokens completely belonging to the Asset Token class seems unreliable except for Bitcoin.

Ecological Prosperity of Public Blockchain

To validate a utility token on public blockchain based on supply & demand within its own network, we would prefer to have a flexible descriptor — Ecological Prosperity Descriptor — to quantifiably describe the overall situation, which is made up with various Dapps, their number of accounts, usage, asset liquidity, etc. Since asset liquidity of ecological applications is difficult to measure in a decentralized fashion, the quantification is difficult. However, one of the key elements of our desired Ecological Prosperity Descriptor can be determined by the market, which, in our case, is the number of SERO tokens needed to be pledged by applications. This foundation of pricing is far more reasonable than the gas consumption cost of asset transactions. More importantly, since any application development will surely go through its own different cycles, it is more reasonable to judge the entire ecosystem by pledged tokens under applications, so whatever stages the individual applications are in, the token emission should match this realistic demand and encourage their growth. With such a context in mind we deem adjustments of token emission necessary, justifiable, and sensible.

Related news

Search news

Recommended news

The SERO Foundation officially invests in the RHINO Trading Platform

2020-04-26

SERO successfully passed the code audit of IT Security Firm KnownSec.com

2020-04-05

Announcement of Staff Change

2020-02-10

Introducing SERO 2.0- The Rise and Vision-Part 3

2020-03-20

Introducing SERO 2.0- The Rise and Vision-Part 2

2020-03-20

Introducing SERO 2.0- The Rise and Vision-Part 1

2020-03-20

SERO Tokenomics and Circulation Statistics (as of 2019.4.30)

2019-04-30

SERO Mainnet Launch : GPU Mining and New Algorithm

2019-05-31

SERO Guild Reward Pool Adjustment Plan Announcement and SERO Association

2019-04-25

SERO Mining Association Reward System

2019-01-23

SIP1 and BETANET-R5 Release

2019-01-23

SERO BETANET-Release is launched!

2019-01-08

SERO BETANET-RC1(v0.3.0-beta.1) Released

2018-11-21